On June 30, 2017, I co-presented a breakout session entitled, “Formative Assessment: Flourishing or Floundering?” with two of my education heroes, W. James Popham and Margaret Heritage, at NCSA, the National Conference on Student Assessment, in Austin, Texas. This post summarizes my stance on this important topic:

Formative Assessment: Is it still flourishing as it was in recent years?

My position is yes, it still is, but only if and when certain key factors are in place. And the first factor is the clear understanding of formative assessment’s chief purpose and function.

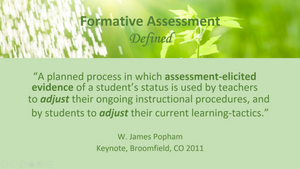

In 2011, I heard W. James Popham, foremost expert on assessment, define formative assessment and its true purpose as follows:

Because we are talking here about formative assessment, that adjective clearly indicates that the assessment is taking place while students are in the process of learning. Formative assessment evaluates a student’s current understanding or ability before, during, and after instruction. But that’s only part of it. The assessor and the assessed then need to do something with the results. If they don’t, this but adds further grist to the mill of popular opinion that as a nation, we are “over-testing and under-assessing” our students.

We Have a Clarity Problem

Some would say that in many U.S. schools today, there is a clarity problem. Others would go so far as to call it a clarity “crisis.” Teachers, and as a result, their students, are not crystal clear about what the learning outcomes are. Consequently, instruction is not as focused as it should be, and student learning is not as intentional as it could be.

Ask students what they’re learning, and most likely they will tell you what they’re doing. They confuse the context for learning (the means) with the learning itself (the end). The book, the project, the experiment, the activity—these are the means to the end, not the end itself.

Clarity: The Heart of Formative Assessment

In Dr. Popham’s 2011 keynote, he emphasized the vital need for clarity: “Clarity of intent is most important. If teachers know exactly what they want students to know and do, it will impact everything they do when designing instruction and assessment.”

Professor John Hattie’s research (Visible Learning, 2009) has shown teacher clarity to approximate a 0.75 effect size, meaning it has the potential of boosting student learning to the equivalent of nearly two years of growth in one academic school year.

He defines learning Intentions (Visible Learning for Teachers, 2012) as “what it is that we want students to learn, and their clarity is at the heart of formative assessment. Unless teachers are clear about what they want students to learn (and what the outcome of this learning looks like), they are hardly likely to develop good assessment of that learning.”

Components of Clarity

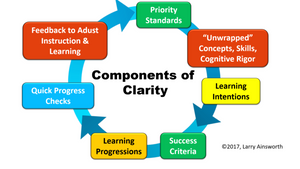

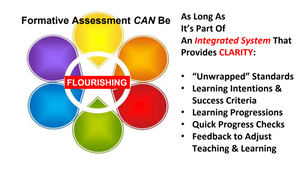

If assessment is to flourish–and not flounder–it cannot be an isolated, summative practice with no further purpose than the assigning of a letter grade to a pop quiz, a test, or an exam at the end of a marking period. Formative assessment, the focus here, must be part of an integrated system that has its foundation in CLARITY, as represented in this diagram:

- Priority Standards: “Unwrapped” or deconstructed standards to pinpoint what students are to learn and be able to do with identified levels of cognitive rigor;

- Learning Intentions: “Unwrapped” standards restated in student-friendly language without losing any of the rigor; the larger learning targets for a unit of study;

- Success Criteria: Specific descriptors of what students need to demonstrate in order to show they have achieved the Learning Intentions;

- Learning Progressions: The “building blocks” of instruction, presented in daily lessons, that clearly lay out a pathway to the larger Learning Intentions;

- Quick Progress Checks: Formative assessments matched to lesson-specific learning progressions that provide evidence of student learning; and

- Feedback: Use of the formative assessment results–the evidence of learning–to inform and adjust teaching and student learning tactics or strategies.

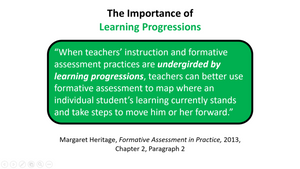

Feedback provides evidence of learning, but if the evidence is faulty, the inferences teachers make will also be flawed. That is why quality assessment design is so critical. Margaret Heritage wrote: “Without quality evidence, teachers may not be able to take the right kind of action that will lead to positive consequences for learning.” (Formative Assessment: Making It Happen in the Classroom, 2010).

Here she emphasizes the relationship between learning progressions and formative assessment and how teachers can use student results most effectively:

Formative Assessment Can Still Continue to Flourish IF…

Teachers and students using formative assessment results to make needed adjustments is both timely and timeless. This is why I’m of the opinion that formative assessment is as important today as it ever was (timely) and will continue to be so (timeless)—as long as it’s part of an integrated system that provides CLARITY to both teacher and student.

Where Is Formative Assessment Flourishing?

In next week’s post, I’ll share key factors needed in order for formative assessment to flourish, and showcase one large school district in Illinois that is reaping impressive results by the continued implementation of formative assessment as a system founded on clarity.